by Heather Bell, MPH, RD,LDN

It won’t come as a surprise to anyone who knows CNC 360 that we endorse the concept of Health At Every Size. We challenge the idea that weight = health, and we encourage our clients to seek out accurate and balanced information about nutrition and wellbeing. One of the questions we get, however, is “Does the research actually support the idea that weight-centric approaches to health aren’t necessary?” Another is, “Why don’t I ever hear about research studies that support Health At Every Size?”

It won’t come as a surprise to anyone who knows CNC 360 that we endorse the concept of Health At Every Size. We challenge the idea that weight = health, and we encourage our clients to seek out accurate and balanced information about nutrition and wellbeing. One of the questions we get, however, is “Does the research actually support the idea that weight-centric approaches to health aren’t necessary?” Another is, “Why don’t I ever hear about research studies that support Health At Every Size?”

In fact, there IS lots of research that argues in favor of HAES approaches. https://www.sizediversityandhealth.org/content.asp?id=161. And although there are many factors which affect whether and how certain research is publicized, one of the most troubling is this:

Sometimes researchers are so committed to the belief that weight = health that they don’t focus on what their own data are actually showing them. In the face of research results which strongly demonstrate that other health factors have a much bigger influence on the risk of illness and death, these researchers still conclude and recommend that higher weights are risky, and that traditional weight management approaches (everything from diets, to medication, to surgery) should be advocated.

And what happens when media outlets are presented with these research papers? Are they going to be able to go through the study and look at how different the actual data is is from the story that the researchers have chosen to tell?—No. They’re simply going to report the published conclusions of the study, thereby reinforcing the public (and clinical!) perception that focusing on weight management in disease treatment and prevention is just good medicine.

Let me show you an example of what I mean. The table below is taken from a research paper published in 2017 in The European Heart Journal.* It involved a meta-analysis of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study (EPIC-CVD). It included 520,000 people who were followed for 12.2 years, and it looked at 7,637 coronary heart disease cases. (Don’t panic if you’re not a statistics-geek! I’m going to take you through the table step by step.)

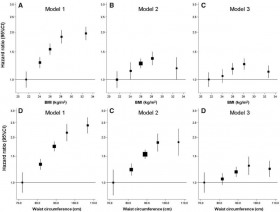

Pictures A, B, and C are presenting the hazard ratio–the risk of developing coronary heart disease (CHD)  depending on which Body Mass Index (BMI) group you are in. A hazard ratio of 1.0 means that no additional risk of developing heart disease is expected.

depending on which Body Mass Index (BMI) group you are in. A hazard ratio of 1.0 means that no additional risk of developing heart disease is expected.

All of the models accounted for age, smoking, physical activity, dietary quality, calories, alcohol consumption and education levels, since these are factors which can independently affect someone’s risk of developing CHD. Each model then focused on other factors which might affect the risk of heart disease.

Model 1A shows the predicted risk of developing CHD based upon BMI category. If we only looked at this picture, we’d walk away from this article believing that the data demonstrated a sharp increase in heart disease risk as BMI increased—anywhere from a ~130% to an almost 200% increase in risk. That’s kind of scary, right?

But look at Model 2B. In that data model, the researchers looked not only at BMI, but waist circumference—in other words, whether someone carries their weight as an apple or a pear. Now the data shows a different picture—that increasing BMI accounts for a lot less CHD risk, because WHERE we carry our weight makes a big difference in our risk of heart disease.

And look at Model 3 C! This model accounts for BMI, waist circumference AND metabolic fitness factors—things like blood pressure, cholesterol, good cholesterol, and family history of diabetes. When you add metabolic fitness to the picture, the effect of which BMI group you’re in drops hugely again—meaning that again, it’s THESE factors, not only our BMI, that are responsible for the increased risk of heart disease.

A similar story is being told in the bottom row of data models: Increasing waist circumference does predict an increased risk of heart disease, but when metabolic fitness is accounted for, the risk for heart disease based on waist circumference alone changes significantly.

That’s what the data showed. But what did the researchers conclude?:

“Our results suggest, that, even in the absence of multiple traditional CVD risk factors (smoking, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol), weight loss strategies through intensive lifestyle advice (diet, exercise, and behavior modification) or medical therapy (orlistat or bariatric surgery) should be recommended for obese patients to try to achieve and maintain a healthy body weight to decrease CVD risk. Overall, these results support a population-wide strategy for prevention of obesity and overweight regardless of the initial metabolic health status of individuals.”

Translation: Even if there are no evidence-based risk factors for heart disease present, obese individuals should be encouraged to engage in the entire gauntlet of traditional weight management approaches. Moreover, these results suggest that the entire population should focus on weight prevention, regardless of how otherwise healthy they may be.

What?! What?!

We know from research, and from the stories that patients bring in to our offices every day, that engaging in traditional weight management approaches is seldom a benign or harmless experience. At a minimum, it tends to leave people in a much more conflicted headspace with respect to food and movement; at its worst, it creates irreparable physical harm and actually INCREASES people’s risk factors for things like heart disease. So why is it acceptable for researchers to continue to blithely recommend it, even in the absence of health concerns?

It isn’t.

OUR take-home message is this: Many people are being made to feel anxious about their health based upon a very narrow focus on weight/BMI. But weight/BMI alone doesn’t accurately predict health risks, and focusing on weight alone is triply problematic. 1) It increases distress and pressure for individuals who, while in larger bodies, don’t possess any of the other, more important risk factors, 2) It doesn’t allow for a dialogue about the risk factors that might make the biggest difference in the actual prevention of chronic disease, and 3) It increases the likelihood that people will engage in weight management practices that are ultimately to their detriment.

At the end of the day, we come back to a health-focused paradigm: Be informed about your body; know what kinds of self-care with food, movement, and stress-management create health and well-being for you. If you’re dealing with health issues, get accurate, balanced information about how to take effective action in order to live well and feel your best. And lastly, keep weight in perspective; it is only one of many factors which can inform our understanding of health and health care.

* Lassale, C. (2017). Separate and combined associations of obesity and metabolic health with coronary heart disease: A pan-European case-cohort analysis. European Heart Journal, 39(5), 397-406. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx448XXXX